Module 6: The Indian Wars

- Prof. Klann

- Sep 7, 2020

- 15 min read

In Module 3, we started discussing examples of violent conflict between Native nations, American settlers, and the US Army in the West. In Module 6, we'll pick up this discussion and example conflict on the Plains between the US and powerful Native nations in the late nineteenth century. We'll look at how the US tried to remove Native people from the Plains, and Natives' responses. Specifically, we'll be focusing on the Comanche and the Lakota. (Check out the annotations for more details on the language I'll be using to describe Indigenous people in this module blog post.)

Two questions will guide this module blog post:

How did powerful Native nations like the Comanche and Lakota resist American encroachment onto their land?

What were the policies and events which contributed to American “subjugation” of Native nations on the Plains?

Let's get started.

Part I: US Indian Policy and the Comanche

The relationship between the US government and Native tribes in the 19th century can be characterized as one of violence and tension surrounding American desire for Native land. For example, the Indian Removal Act, signed into law on May 28, 1830, authorized the president to enter into negotiations with all the Eastern tribes. If the tribes agreed, removal treaties would stipulate an exchange of their land in the East for equal or greater amounts in the West.

Under the Indian Removal Act, the US would pay for moving costs, provide support for their first year of residence in the West, and compensate individuals for the value of improvements they had made to the land they left behind. As some of you are probably familiar, removal was devastating for tribes, who were often left with no choice but to sign removal treaties and then forced to march to their new homelands in horrible conditions, resulting in disease and death.

In the map below, you can see the forced removal routes of five Southeastern tribes from their homelands to Indian Territory, present day Oklahoma: the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole. The Cherokees' relocation is known as the Trail of Tears.

Tribes were often forced to sign removal treaties because American settlers had already encroached on their territory. Additionally, southern states like Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi passed laws forcing Native people under the jurisdiction of the states. The Cherokee Nation challenged the legality of removal, and argued that it was unconstitutional for the states to infringe upon the rights of the tribe to govern itself. In an influential Supreme Court case, Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, the Cherokees challenged that Georgia had no right to impose on their land or force them under the jurisdiction of Georgia law.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court decided that Native nations were not “foreign nations,” but “domestic dependent nations,” and their relationship to the US was like that of a “ward to its guardian.” This phrase becomes very important at the end of the nineteenth century, as we’ll see in our next module, Module 7.

Thus, significantly, the US did not view Native nations as foreign entities, but as “dependent” nations who were by definition “lesser than” Americans: less civilized, more “savage.” We’ll see the violent effects of this philosophy coming to a head in this module.

Violence on the Plains After the Civil War

After the Civil War, thousands of American migrants began to traverse the Great Plains in search of homesteads and resources, as we’ve seen in previous modules. The federal government made only token efforts to negotiate with Native nations on the Western Plains for right-of-way across their lands.

Migrants were essentially trespassing, and violence became routine. Sometimes American actions triggered bloodshed. Other times, migrants stepped into existing conflicts.

For example, after the Sand Creek Massacre, mentioned in Module 3, Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and their Lakota allies declared war on the US. They attacked wagon trains, stagecoach stations, military posts, and ranches across eastern Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming.

A group of Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota militants called the Dog Soldiers refused to negotiate any peace treaties.

By 1866, the central plains were a site of unrestrained violence.

The Lakota waged their own war against the US Army, which had been constructing unauthorized forts to secure a trail that led from southeastern Wyoming to the gold camps of Montana, cutting right through Lakota hunting grounds.

Escalating conflicts, raids, and reprisals erupted into full-scale war in 1866. Late that year, the Lakota attacked eighty soldiers near Fort Phil Kearny in Wyoming.

This was the army’s worst defeat in the West put to that point. It forced Washington to address the turmoil on the Plains. However, having just finished a major war, the American public demanded a humanitarian rather than a military solution to the conflict.

Congress created the Indian Peace Commission, which was designed to negotiate peace treaties with the Plains Indians. The Commission focused on the crucial section of the Plains between the Platte and Arkansas rivers, the projected settings for the Union Pacific and Kansas Pacific railroad lines.

In order to resolve the conflicts—and clear Native people out of the way for the development which would come with the railroad—the commissioners set out to relocate Native nations in two reservations. The Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho, and Crow would share a reservation in the Black Hills of Dakota Territory. The Comanche, Kiowa, Naishan, Southern Cheyenne, and Southern Arapaho would be removed to western Indian territory (Oklahoma). The government envisioned that once they were confined to isolated reservations, Native people could be taught to live in houses, become farmers, and speak, read, and write English. [1]

Poll #1:

Think about the goals of the Indian Peace Commission, and the decision to focus on negotiating with tribes who claimed the projected settings for the railroad lines when answering the first poll question:

In your opinion, to which did Native people on the Plains pose a bigger threat? Expansion of American economic development? or the expansion of American homesteads? Answer the poll below, or check it out here.

Comanches and the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek

In 1867, more than five thousand Comanches, Kiowas, Naishans, Cheyennes, and Arapahoes congregated at Medicine Lodge Creek (present day Kansas) to meet with the US Peace Commission.

The Commission pressured the Comanche and Kiowa to accept a 5,500-square-mile reservation in Indian Territory. There they would have access to physicians, blacksmiths, millers, engineers, teachers, and schools—part of a “civilization” program to transform the tribes into small farmers.

They could also hunt within the bounds of their territory, as long as the bison remained. However, ownership of the land off the reservation would fall to the US.

The US wanted the Comanche and Kiowa to relinquish 140,000 square miles, in exchange for $25,000 per year for three decades. The Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Naishan received similar offers.

At this point in time, the Comanche were one of the most powerful entities in the West. Their range of power stretched from West Texas to New Mexico, over much of the Southern Plains. They gained power and influence through the breeding, stealing, and trading of horses; stealing cattle from settlers; hunting buffalo; and raiding European, American, and other tribal groups.

The Comanche, Kiowa, Naishan, Cheyenne, and Arapaho ended up signing treaties with the US. However, as Pekka Hämäläinen writes in Comanche Empire, they maintained a fundamentally different understanding of those treaties than the US commissioners.

We can see the Comanches’ opinion about the treaty in a speech made by Parusemena, a Comanche leader: “The Comanches are not weak and blind, like pups of a dog when seven sleeps old. They are strong and farsighted, like grown horses…When I get goods and presents I and my people feel glad, since it shows that he [the president of the United States] holds us in his eye. You said that you wanted to put us upon a reservation, to build us houses and make us medicine lodges. I do not want them…I want to die there [on the plains] and not within walls.” [2]

Parusemena offered a counterproposal: Comanches would permit limited right-of-way across their land, in exchange for annuities (a fixed sum of money paid each year). But, he and other Comanches categorically rejected any demands the Americans made that would have jeopardized the Comanche way of life.

The stipulations of the treaty were ambiguous. The US interpreted it as the Comanches giving up their claims to the land and accepting a reservation. They were granted hunting rights on a larger stretch of land (with the caveat, “so long as there were buffalo”).

The Comanches interpreted the hunting privileges as evidence of their ownership. In the treaty, the US stipulated that they would keep American hunters from entering the Southern Plains, giving the Comanches the impression the the treaty secured their territorial rights.

The winter after the treaty was signed, thousands of Comanches and Kiowas did visit with a US government agency to collect their annuities. However, only a small fraction stayed to start a life on the reservation. They simply carried on with their traditional ways and policies. They hunted, raided, and traded on the Plains and in Texas for most of the year. In the winters, they moved in larger numbers to the reservation to live on rations. Instead of relocating to the reservation and starting lives as small farmers, they incorporated the reservation into their existing yearly cycle.

Not only did the Comanches and Kiowas fail to relocate permanently onto a reservation, their raiding of horses and cattle wreaked havoc on settlements in Texas. Meanwhile, Dog Soldiers continued their own raids on Americans in Colorado and Kansas, threatening railway construction.

The Senate appointed General William Tecumseh Sherman to administer Indian policy and suppress the violence. Sherman authorized a campaign to drive Cheyennes south, and attack Cheyenne and Comanche camps and villages. The Army built a new soldier town at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to oversee Native people.

In 1869 President Grant introduced a Peace Policy, which advocated for “Christian education” over coercion and brought Protestant missionaries to oversee the reservations. Troops were authorized only to attack and make arrests if Native people had been positively identified as “hostile.”

Peace Policy

The Comanches’ use of the reservation as a seasonal supply base frustrated the agent there, a Quaker named Lawrie Tatum. Tatum wanted to increase annuities to make the reservation more appealing. He also tried to withhold rations from Comanches who he identified as raiders.

However, Comanches resisted his attempts at control. They insisted that only chiefs should accept rations. After receiving them, they would redistribute them among Comanche women, who would take them to their camps, located as far away from the reservation as possible. Tatum was thus restricted to dealing with just a few headmen. The other Comanches became anonymous, meaning individual warriors and raiders could pass through the reservation untracked.

Both Comanches and Kiowas exploited a loophole in the Peace Policy, which specified that the army could not pursue raiders into reservations. They used the reservation as an "asylum."

Although the Comanche were successfully able to manipulate the Peace Policy to serve their own needs, the annuity system was not perfect. Supply shortages were common. Flour was often infested with worms. Traders made Native people pay for goods they were supposed to receive for free. But ultimately, Comanches were able to primarily support themselves without utilizing the reservation or annuities they received from the US.

They capitalized on the growth of Texas cattle ranches. As ranches grew, they were harder to defend against Comanche raiders who could enter and exit the open range pastures undetected. Comanches remained tightly linked to long-standing trade networks of cattle, horses, and goods in New Mexico.

Poll #2:

Did the Peace Policy accomplish what Grant wanted? Was it successful? (You can think about this question from the perspective of the US government, or from the Comanches' perspectives. Explain your answer further in the comments or annotations.) Answer in the poll below, or access the poll here.

By the early 1870s, federal officials and military elites viewed the Comanche situation as a stinging embarrassment for the US. The Peace Policy seemed to have made the US hold on Native people and the Plains weaker, rather than stronger. They decided to change tactics.

The US Army needed large numbers of American soldiers to defeat the Plains tribes, who were highly motivated, and highly mobile. However, the public in the east was weary of war. Young men were unlikely to volunteer to fight on the Great Plains for low pay. The army’s main instrument was the light cavalry, composed of ten regiments, about 5,000 men in total.

The army embarked on a campaign of total warfare. They destroyed Comanche winter camps, food supplies, and horse herds. Targeting civilians and economic resources was the quickest way to subdue the warriors. In addition, although the Army came with a relatively small number of troops, they had enormous resources—technology, supplies, an elaborate system of communication, and the motivation to expand the nation through conquest.

Cavalry units from Texas (who hailed from the same regions victimized by the Comanches) targeted Comanche supplies and took women captive in order to force Comanches to agree to stop raiding. Additionally, holding women captive was a deliberate way of disrupting Comanches’ preparation of their winter camps.

Additionally, after tanners in Philadelphia had perfected a process of turning bison hides into an elastic leather for machine belts, a growing demand for hides sent a swarm of hide hunters to the Plains to slaughter buffalo. Just two years after this process had been invented, the central plains were almost devoid of buffalo.

The hide hunters then turned to Comanche and Kiowa hunting grounds, although it would mean violating the terms of the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek.

Army units did nothing to enforce the treaty line. In fact, they did the opposite: they provided protection, equipment, and ammunition for hunting squads. As a result, the Comanches were devastated. They found the Plains littered with skinned, rotting buffalo carcasses. With their winter camps and food supplies already targeted by the military, they faced starvation.

Devastating the buffalo meant that not only was the Comanche’s economic livelihood destroyed, but their way of life was destroyed too.

The last attack of the US Army on Comanches came on September 28, 1874. A cavalry unit surprised a village, sending the people there to scatter on the open plains. The army then destroyed the camp, burning tipis, robes, blankets, thousands of pounds of meat, flour, and sugar. They shot most of the horses. After this last attack, most of the Comanches retreated to the reservation, this time to stay.

Poll #3:

Thinking back on the conflict between the Comanche and the US, answer this question: which of the following posed the greatest threat to Comanche power on the Plains? The reservation system, the US Army, or buffalo hunters? Answer the question below, or access it here.

Part II: Lakota Resistance

For Part II, we’ll switch to the north to examine the experience of another powerful Plains tribe: the Lakota, whose territory encompassed present day western South Dakota, and parts of Nebraska, North Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming. The Lakota are also known as the Sioux.

In 1863, the US Army established the Bozeman Trail, a trail that led from southeastern Wyoming to the gold camps of Montana, cutting through Lakota hunting grounds.

Lakotas and their allies conducted highly mobile attacks against the US. The Lakota gained the upper hand. This series of ongoing conflict was known as the Powder River War, or Red Cloud’s War.

Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868

In 1867, the same year that US Peace Commissioners and the Comanche and Kiowa met at Medicine Lodge Creek, commissioners met with Lakotas to come to the terms of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie.

The treaty was viewed by many Lakota as a victory. It banned Americans from entering Lakota land without permission, precluded any further land sales without agreement from 75% of Lakota males, and recognized a massive stretch of land of the northern Great Plains as Lakota land.

The Great Sioux Reservation would encompass 25 million acres, including all of western South Dakota, and smaller pieces of Nebraska and North Dakota. In addition, the treaty specified that additional parts of “unceded territory” in Nebraska, North Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming would be areas where Lakotas were free to travel and hunt.

Sitting Bull, a well-respected Lakota warrior and political leader, was a staunch opponent of all US government programs. He refused to sign the Treaty of Fort Laramie, remaining in the “unceded” western territory. Sitting Bull’s followers, which we could call “nontreaty” Lakotas, were labeled as “hostiles” by the US Army and government officials.

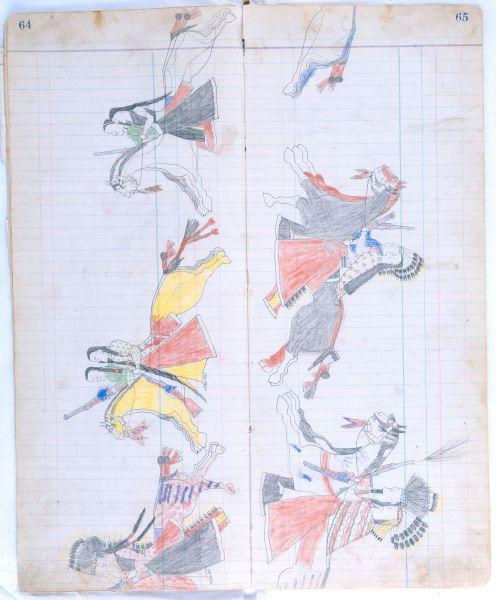

In this post, I’ve featured some of Sitting Bull’s ledger art, a Plains Indian form of illustrating past events. These images were used as tools to recount events in the present. They are essentially histories told through pictures, and have their roots in hide painting. The ledger drawings shown in these slides were created using pencils and paper from account ledgers. Essentially, ledger art is kind of a side effect of the buffalo herds by Americans after the Civil War. Instead of creating these drawings on hides, they were created on paper and canvas.

In 1874, the New York Times, published an article describing American frustrations at the resistance of the “hostile” Lakotas : “…multitudes of Northern Indians, variously estimated at from 10,000 to 15,000 in number, who come there in the Winter to avail themselves of the Government rations dispensed at those agencies. These Indians are turbulent and unruly, and combined with 11,000 to 12,000 Indians who properly belong to these agencies, give a vast amount of trouble to the agents, and utterly defy all attempts to count them, with a view of issuing only the lawful number of rations.”

By the mid-1870s, only about 10 percent of all Lakotas were living off the reservation in those unneeded territories full time. Relations with the US worsened when gold was discovered in the Black Hills. The US sent a military detachment to investigate, violating the terms of the 1868 treaty. Miners began to flood in, and the US made only nominal efforts to stop them.

In 1875, the military suspended their efforts to stop the trespassers, and instead attempted to force another land cession from the Lakota. The Lakota refused to sell. In early 1876, war broke out between the Lakota and the US Army as the Army tried to force all Lakotas to relocate to the reservation.

Lakota Sun Dance

In addition to military resistance, the Lakota also turned towards an important religious ceremony for strength: the Sun Dance. The Sun Dance offered warriors an opportunity to demonstrate personal heroism in the interests of tribal unity, and brought Lakota people together to seek favor from Wakan Tanka, the sacred animating force of the universe.

To participate in the Sun Dance, men would volunteer to have sticks inserted into their skin and be attached to a twenty-foot pole. Warriors would then dance, deprived of food, drink, or sleep, until the skewers tore through their flesh. Successful dancers prepared themselves to receive a prophetic vision as a result of this experience.

By giving their body up to the spirit of the universe, the dancers themselves became sacred, their spirits attached to Wakan Tanka. The US government denounced the Sun Dance as “heathen” and classified it as self-torture. But, Lakotas argued that this was a spiritual practice whereby dancers would realize through the dance the wholeness and unity of all things. [3]

In June 1876, Sitting Bull participated in the Sun Dance during a large Lakota gathering. He had a vision of soldiers and Natives falling upside down into the Lakota camp, which he interpreted as a vision of the Lakota and Cheyenne destroying the American army. When the Sun Dance ended, the camp moved to the valley of the Little Bighorn River. By the end of the month, they were joined by other Lakotas and allies, numbering 1500 to 2000 warriors.

Word Cloud #1:

What impact do you think the Sun Dance had on the spiritual and/or military power of the Lakota? Contribute an answer in the word cloud below. Or, access the word cloud here.

Battle of Little Bighorn

The Seventh Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, discovered the abandoned Sun Dance camp and noted pictures that had been drawn in the sand. One of Custer’s Native scouts noted that one of the drawings indicated that the Lakotas were sure of winning a battle with the soldiers. [4]

On June 25, 1876, seven Lakota tribes, a large contingent of Cheyennes, and others were attacked by Custer’s forces. Initially, they were thrown into disarray. However, they soon regroup and launched a determined counterattack on Custer’s forces, utilizing bows, arrows, knives, hatchets, clubs, and forty different kinds of firearms. In addition to their superior numbers, the Native forces also outgunned Custer’s command. Custer and 268 of his men were killed in the fight. This event shocked the nation, and Americans began to cry for a military response.

After Custer’s defeat, the US Army sent additional troops, built new forts, and took control of the reservations. Sitting Bull led his forces to sanctuary in Canada in early 1877. On May 6, 1877, the Lakota leader Crazy Horse surrendered with over 1,000 of his followers.

Despite his surrender, hostility once again broke out in the summer of 1877. As a result of a miscommunication and a scuffle, Crazy Horse was killed while he was being arrested by the a government agent.

The rest of the Lakota were faced with a difficult choice after Crazy Horse’s death. Congress decreed that until they surrendered all rights to the Black Hills and unceded territory, they would receive no subsistence. Although three quarters of Lakota males did not formally agree to this arrangement, Congress interpreted their decision as an acceptance.

After returning to the US in 1881, Sitting Bull and his followers were imprisoned at Fort Randall for two years. He was quite a celebrity. On the way to Fort Randall, Sitting Bull and his group docked at Bismarck, attracting hundreds of residents to come and see him and shake his hand. He began to charge between $2 and $5 for his autograph.

The American population knew his name from newspaper accounts, including the republications of his own ledger art. So many letters poured in from around the country that in 1882, a colonel at Fort Randall was assigned to take charge of his mail. Reportedly, he would not answer a letter or send an autograph unless the sender sent a dollar in advance.

While imprisoned, he created a series of ledger art as a way of showing gratitude to Lieutenant William Tear, who had supplied him and his children with blankets and clothing before the government’s supply came in.

Although Tear tried to get Sitting Bull to recount his role in the Battle of Little Bighorn, he refused. He continually asserted that he was fighting in defense of his homeland. He emphasized: “I did not hunt Custer. I thought I had a right to protect my own women and children. If he had taken our village he would have killed our women and children. It was a fair fight.” [5]

If you're interested in the ledger art in this module, check out more ledgers at the Plains Indian Ledger Art database.

Conclusion

Comanches refused to confine themselves onto a reservation, instead retaining their economic power by raiding and bringing government annuities and the reservation into their existing way of life. Lakotas continued powerful spiritual practices like the Sun Dance, which provided cultural and religious resistance to American military campaigns.

Military campaigns, including total warfare—the destruction of crops and economic power and the slaughter of buffalo contributed to the devastation of the Comanches’ economic power. The Lakotas faced concentrated Army attacks after they defeated Custer’s forces at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Citations

[1] Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008). 321-322.

[2] Hämäläinen, Comanche Empire, 323-324.

[3] Arthur Amiotte, “The Lakota Sun Dance: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives.” in Sioux Indian Religion: Tradition and Innovation, edited by Raymond J. DeMallie and Douglas R. Parks (Norman, OK; London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1987), 88-89.

[4] James O. Gump, The Dust Rose Like Smoke: The Subjugation of the Zulu and the Sioux 2nd ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016), 3.

[5] Candace Greene, “Verbal Meets Visual: Sitting Bull and the Representation of History,” Ethnohistory 62, no. 2 (April 2016), 235.

The policy established by Grant was not very succesful. Grant and the United States tried to take advantage of the Comanche people by kicking them out of their land. He tried to slowly encourage them to enjoy life on the reservation although they were resistant to change. They managed to live their life more closely to how they used to live it. He hoped to make them rely on the American way of life and the American system. It was somewhat unsuccessful however due to the Comanche's impressive ability to take care of themselves.

Did the Peace Policy accomplish what Grant wanted? Was it successful?

The peace Policy wasn't successful since the US government were selfish and cared more for themselves in the process. They took advantage of the Comanche people similar to other instances.

In your opinion, was the Peace Policy successful? In my opinion, the peace policy was not successful. It was seen as successful to Comanche to manipulate to fulfill his own needs. Everything turned out to be the opposite of the policy as read. Natives had to pay for good that should have been free. Flour has worms. Comanches stayed close to traders to survive.

As for the Peace policy being successful, I thought it wasn't. It did not serve to give both sides what they really wanted. Grant wanted to end hostilities, his policy was merely used for the loopholes found within it. As raiding parties continued to raid and attack and retreat into these sanctuaries of reservations. The Natives lost land and then had to be restricted to certain areas to be somewhat free. As well as having to deal with buffalo hunters that were protected by soldiers. The hunters fanatic killing spree destroying the native's source of food and other commodities from animal parts.

Hi everyone! I noticed two (slightly conflicting) themes in the response to the question about the success of Grant's Peace Policy. Some of you argued that it wasn't successful because Comanche and Kiowa people were able to manipulate and exploit the policy for their own means, adapting the reservation into existing cycles of movement and resource gathering. Others highlighted the United States' manipulation of the treaty agreements and their refusal to protect Comanche homelands. I think both of these things are true at the same time.

Emma noted that in this time period, tensions were high between both sides. Omar and Peihong both pointed to the threat that Native people on the Plains posed to American economic development. When assessing…